Where the Next 5 Years of Outperformance in SEA Will Come From

Breaking down the structural shifts and what they mean for SEA equities

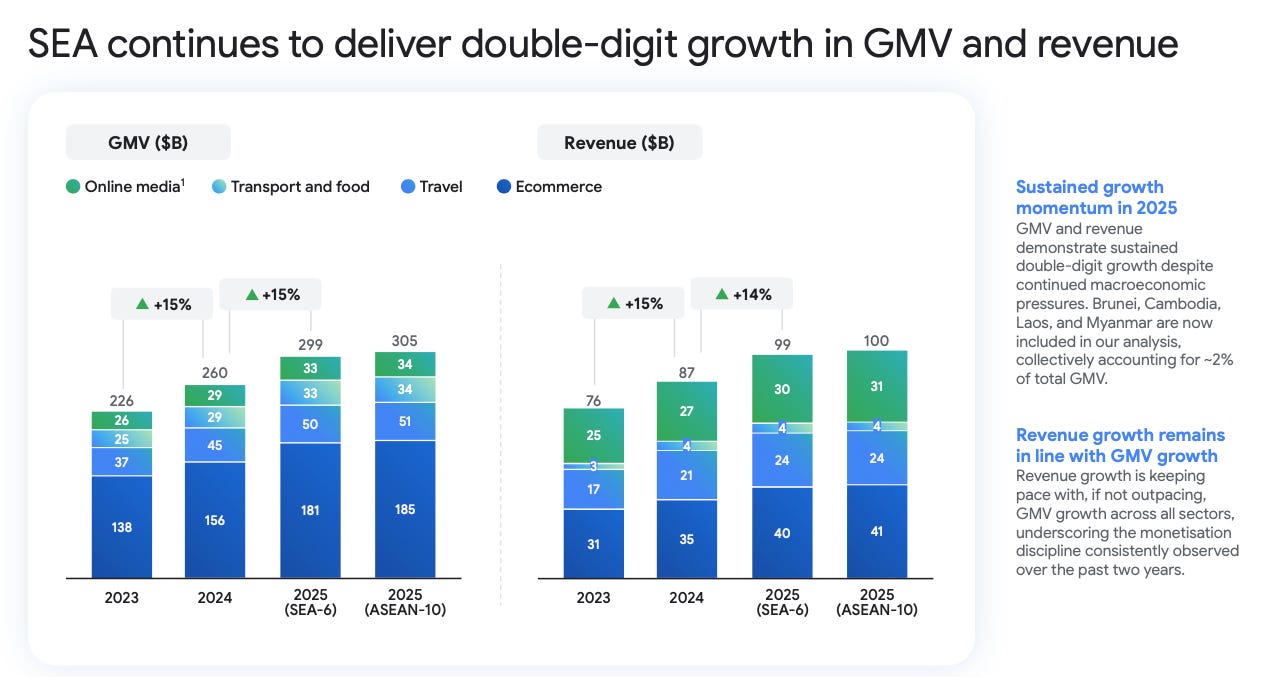

Southeast Asia’s digital economy crossed US$300B in GMV in 2025, nearly 50% higher than what the very first e-Conomy SEA report projected 10 years ago.

A short introduction to the e-Conomy SEA report: this is a landmark annual study of Southeast Asia, particularly focused on the digital economy. It was first launched by Temasek and Google in 2016, with Bain & Company joining as lead research partner in 2019. It tracks and analyses the digital economy of Southeast Asia across several sectors: e-commerce, travel, food & transport, online media & digital financial services.

In my opinion, it is mandatory reading for all SEA investors as it provides an independent, data-driven view of the region’s digital economy. Particularly, how large the opportunity is, trends, investment flows, and challenges.

The e-Conomy SEA 2025 report is 81 pages and covers four major themes. To make the insights more usable for investors, I am breaking it into two parts.

Part 1 focuses on the fundamentals of the digital economy today. It examines the 9 core sectors that currently drive GMV and revenue in Southeast Asia:

e-commerce, food delivery, transport, online travel, online media, payments, lending, wealth and insurance.

In other words, this is the “current state of play”. Who/what is growing, why they are growing and which monetisation strategies are working right now.

Specifically, I will breakdown:

the structural shifts reshaping Southeast Asia’s digital economy

the new monetisation engines driving platform profitability

the AI disruption that will reshape demand and intent

the Digital Financial Services battleground

most importantly for many of us, how each of these forces directly affects Sea Limited and Grab.

Table of Contents

Introduction

Lesson #1: Consolidation is now the main driver of profitability

Lesson #2: Monetisation matters more than GMV growth

Lesson #3: AI is a double-edged sword

Lesson #4: Ecosystem lock-in is key

Lesson #5: Digital financial services are becoming the core monetisation engine

Lesson #6: Cost discipline is structural, not temporary

Lesson #7: Platforms are more important than Meta and Google in SEA

Concluding Thoughts

Introduction

It’s clear to see that the Southeast Asian digital economy has shifted drastically in the past 2-3 years.

The first decade of SEA’s digital economy was largely about:

user growth

convenience

adoption

The companies that performed best in this era were those that could onboard users rapidly, subsidise usage (which required enormous amounts of capital), expand across geographies, and remove friction from previously offline transactions.

That operating environment has clearly changed. Today, nearly everyone who will meaningfully participate in the digital economy is already online. Penetration is high across e-commerce, food delivery, payments, and mobility. Incremental new users are no longer moving the needle, and investors are demanding profits over growth.

Hence, I believe the next decade is about:

monetisation

profitability

AI-driven conversion

regulatory navigation

The companies that can layer multiple monetisation lines on top of their existing and incoming user base will compound faster than those dependent on incremental GMV. Companies that cannot self-fund growth will no longer gain market share through subsidies like before. Profitability discipline has now become a competitive requirement rather than an optional milestone.

Lesson #1: Consolidation is now the main driver of profitability

The first key takeaway and perhaps the one that will shape the next 10 years is that the Southeast Asian digital economy is no longer a land-grab. Competitive intensity has eased meaningfully across e-commerce, transport and food delivery. Several domestic players have withdrawn or merged, while the largest regional platforms have scaled far enough to operate with cost efficiency that smaller players cannot match.

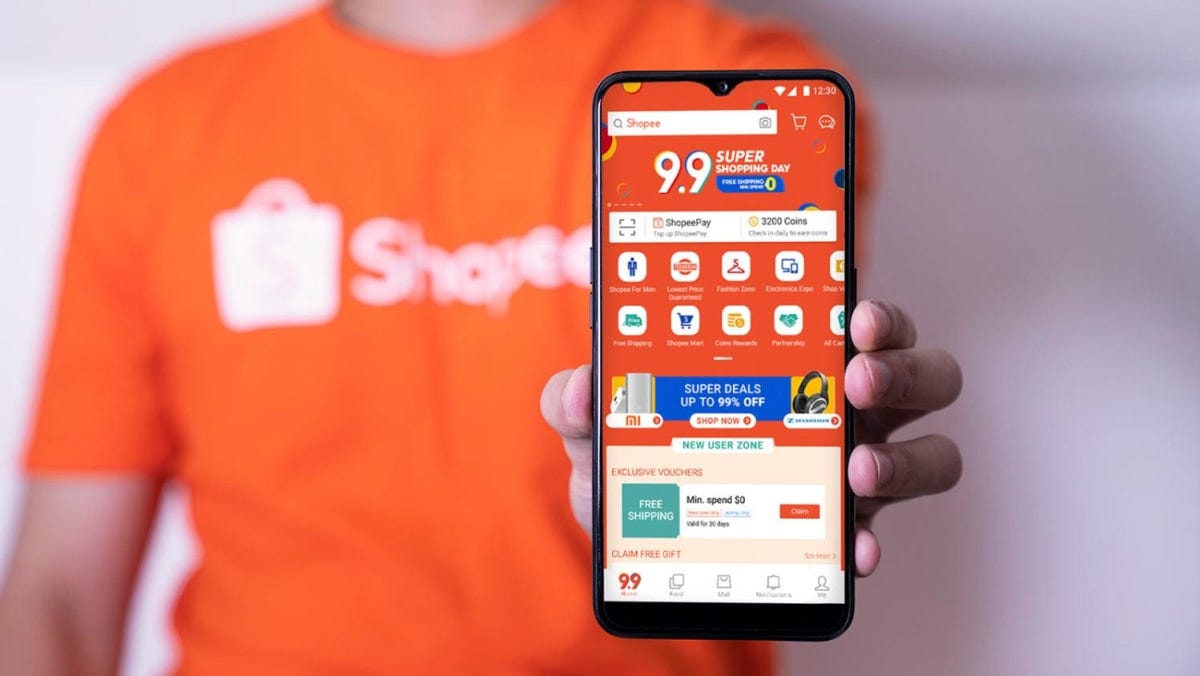

This is evident with the results of Sea Limited and Grab in the past 1-2 years. Sea Limited dominates Southeast Asian e-commerce, with ~50% market share, while Grab dominates transport and food delivery with roughly 4x the share of their nearest competitor.

Each of the major players are now operating at large enough scale to meaningfully optimise unit economics while subsidies are no longer the name of the game.

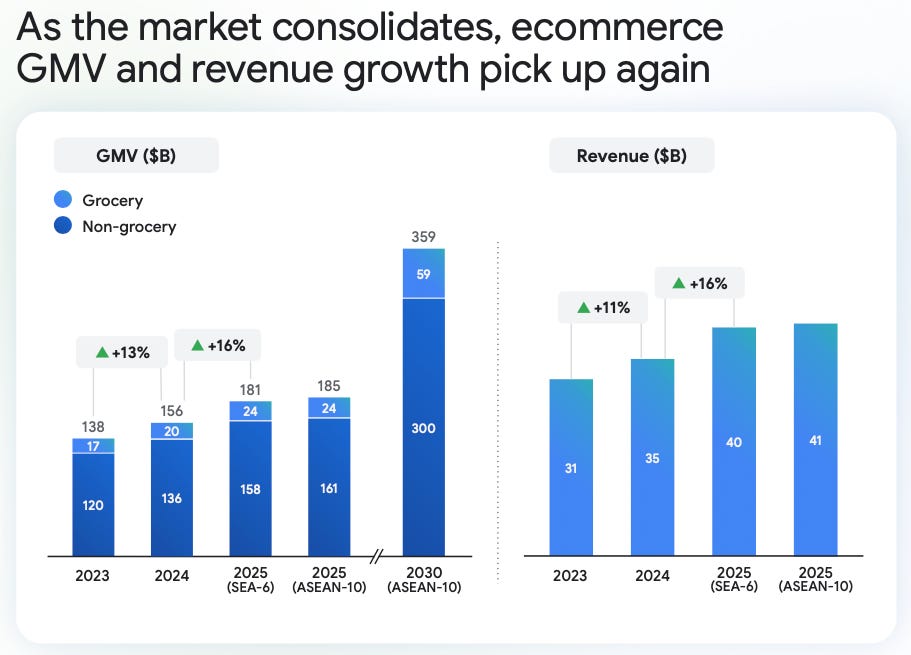

In e-commerce, this has led to a re-acceleration in growth year on year despite a subdued macro-environment. Growth is no longer subsidy driven. It is structurally driven by consolidation and rational competition.

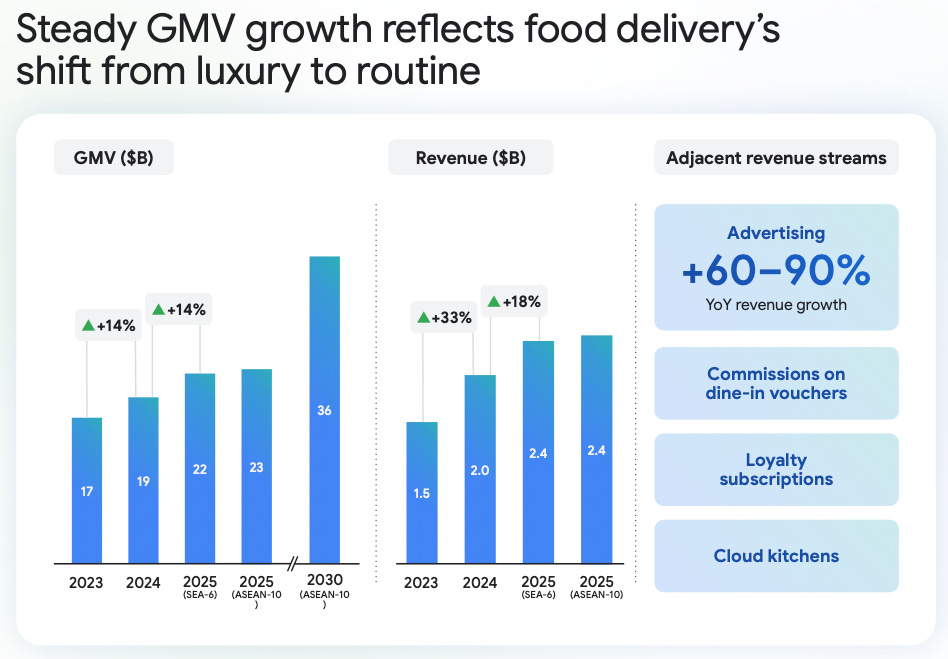

In food delivery, GMV growth has held steady, with the fall in revenue, a feature not a bug. Food delivery platforms have shifted towards everyday affordability, increasingly targeting segments that value affordability by introducing new products and diverse menu options, shifting the service from a discretionary luxury to a more accessible option for a broader consumer base.

This can be seen from Grab’s push for saver deliveries (lower delivery fee in exchange for a longer wait), GrabFood for One (solo-diner friendly options with no small order surcharges) and group order features that allow for sharing of delivery fees. This has led to lower cost to serve and greater profitability for platforms. Platforms have also begun leveraging their reach to become a primary advertising channel for many merchants, whose willingness to pay have increased as results become increasingly more quantifiable. (Grab’s AI Merchant Assistant provides analytics, AI tools, to improve merchant productivity with menu assistance, better promotional targeting, better images etc)

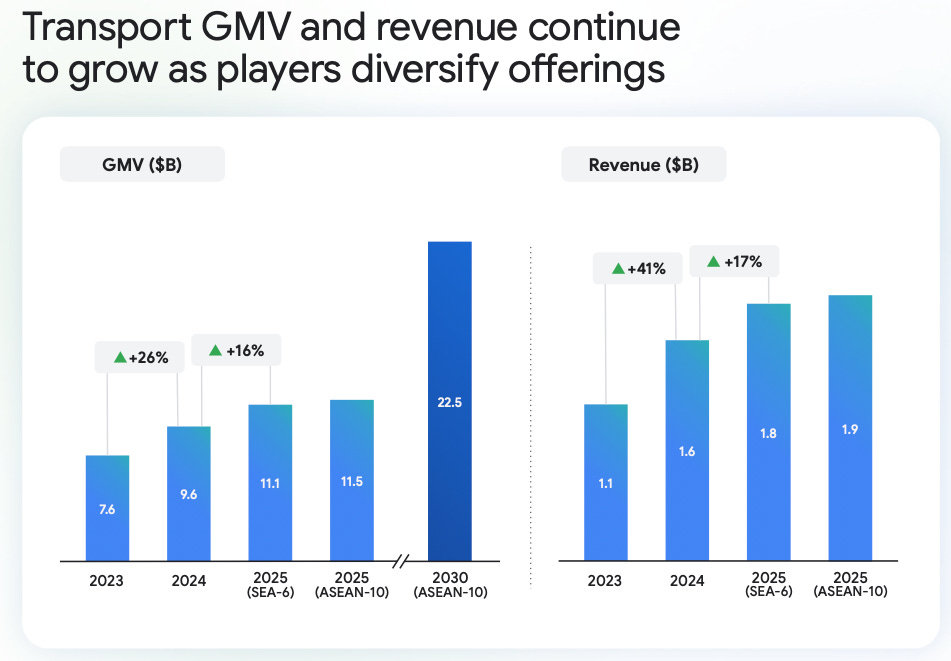

In ride-hailing, GMV and revenue continues to grow at a strong pace with players implementing tiered approaches to appeal to both mass and high-value users. Subscription bundles are also driving frequency, while in-app ads provide a high-margin revenue stream that is driving profitability. As consolidation happens and competition for consumers wanes, consumer incentives are also being reduced, directly contributing to profitability.

What consolidation means for Sea Limited

Shopee is now one of the most advantaged beneficiaries of consolidation in the region. The Indonesia ecommerce market in particular has shifted from a multi-platform battle into a two-platform reality (Shopee v TikTok Shop).

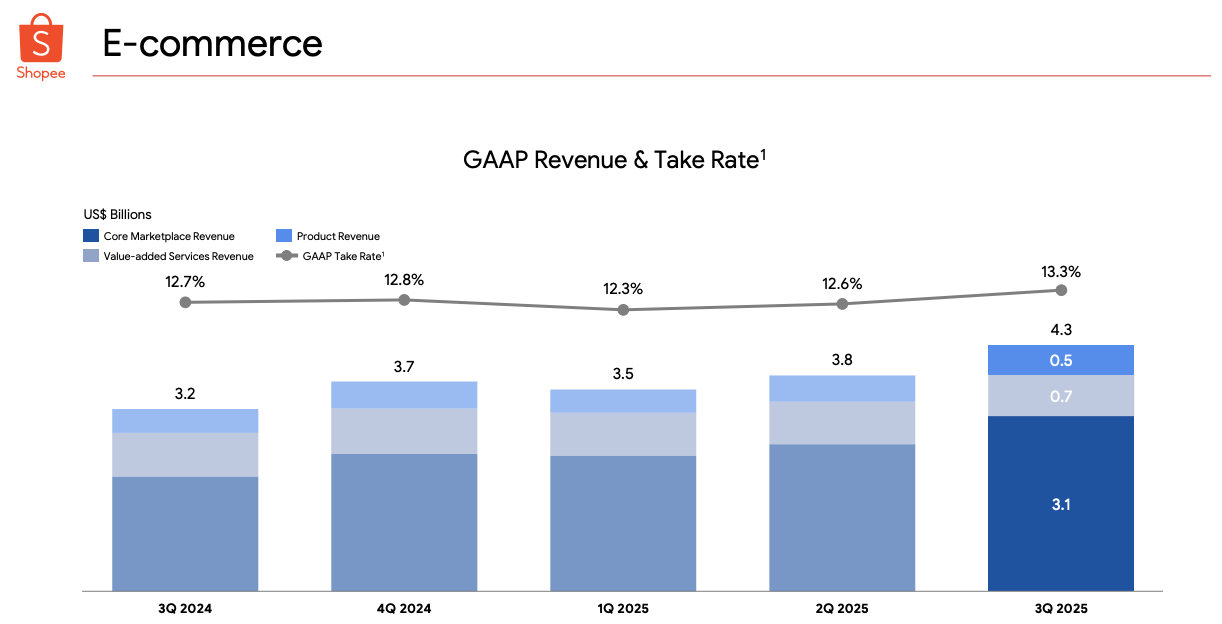

Shopee doesn’t need to spend aggressively to protect share because the competitive landscape has stabilised. As competition wanes, take-rates have risen steadily to 13.3% as of the latest quarter.

What consolidation means for Grab

Grab benefits from consolidation in two separate demand systems at once: transport and food delivery. Both categories were previously impossible to monetise at scale because of the intensity of competition and the fragility of unit economics. Now, both are approaching full commercialisation.

I still believe transport will be a very tough sector to monetise due to the lack of differentiation between products. However, the shift toward subscription bundles is stabilising frequency and with in-app ads acting as an incremental revenue layer on top of rides and deliveries, Grab is set for a major inflection in profitability.

Lesson #2: Monetisation now matters more than GMV growth

The report made it clear that the KPI that matters most in the SEA landscape today has changed. Across sectors, revenue growth no longer trails GMV growth, which is the strongest evidence of rational, disciplined monetisation.

E-Commerce: GMV +16%, Revenue +16%

Food Delivery: GMV +14%, Revenue +18%

Transport: GMV +16%, Revenue +17%

E-Commerce:

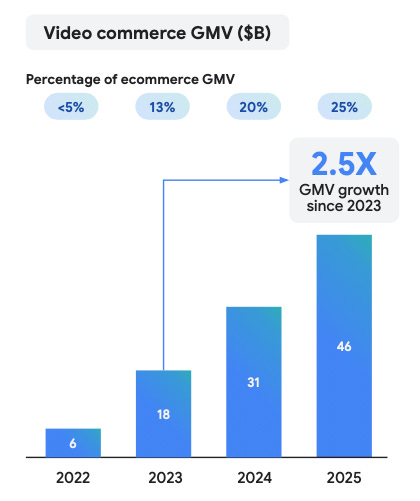

A major driver for e-commerce monetisation is video commerce, which has grown from <5% of GMV in 2022 to 25% in 2025. This has largely been driven by TikTok Shop’s entry into Southeast Asia, driven by the viral nature of its sister app. Shopee, the leader in SEA e-commerce, has also embraced video-commerce early through in-app livestreams and a region-wide partnership with YouTube.

Video commerce excels at promoting high-volume, low-ticket items and relies on impulse engagement rather than couponing. This has improved conversion without increasing cost to acquire users, making it one of the most capital-efficient drivers of incremental revenue.

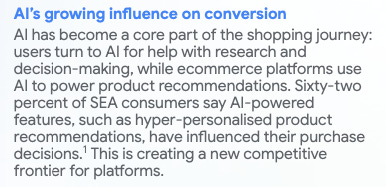

The second driver is the rise of AI-assisted commerce, with 62% of consumers stating that AI recommendations influenced their purchase decisions. Unlike generic discovery algorithms, AI-driven personalisation increases average order value (AOV) and reduces the time from search to checkout by pushing existing users to spend more and more often.

Food Delivery:

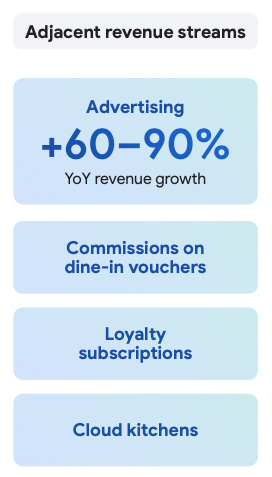

Food delivery is monetising in its own way. Monetisation is being elevated by dine-in voucher commissions, cloud kitchen partnerships and loyalty subscriptions. These are designed to increase the revenue extracted per user across multiple consumption modes, and it has been working well so far. As discussed earlier, platforms are also focusing on the long-tail of vendors that are following in the footsteps of larger competitors by adopting sophisticated advertising solutions. Restaurants now compete for visibility on platforms and unlike consumer incentives, ad revenue scales with no incremental cost.

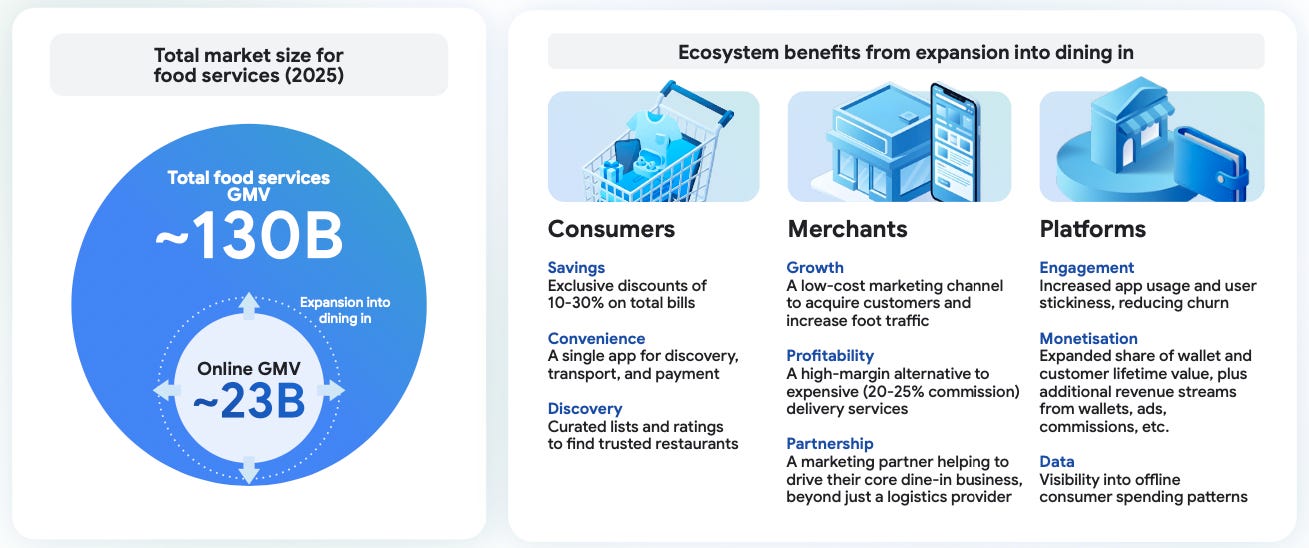

Equally important is the dine-in TAM expansion. Although online food delivery GMV is $23B, total food services in Southeast Asia amount to $130B, more than 5x larger. By enabling loyalty perks and vouchers for dine-in, platforms can monetise offline dining spend without owning kitchens or physical capacity.

Transport:

Transport platforms used to monetise almost exclusively through commissions on rides. That model does not scale linearly because every incremental unit of revenue is tied to a physical ride. The only way to break this constraint is to monetise the user instead of the ride.

Since consumers tend to use transport multiple times a week, it becomes a durable distribution channel for ads, perks, dining offers, payments and loyalty ecosystems. Unlike e-commerce traffic, transport usage is anchored in physical movement, which provides an interruptible moment that is ideal for converting promotional messages.

Lesson #3: AI is a double-edged sword

Of course, we had to cover AI in this piece too. It is reshaping Southeast Asia’s digital economy faster than any other technological wave in the past decade, just like elsewhere in the world.

However, the effect has not been uniformly positive. While AI expands monetisation potential, it also reshapes competitive dynamics, user expectations and cost structures in ways that can both help and hurt platforms depending on their strategy maturity. Essentially, AI is a force multiplier. Platforms that control first-party data and own end-to-end transactions become much stronger with AI. Platforms without deep user graphs risk being commoditised by it.

This is inherently a benefit for Sea Limited and Grab.

As we discussed, the most obvious benefit of AI appears in e-commerce. The report notes that 62% of consumers say AI-powered features influenced purchase decisions while video commerce has grown from 5% to 25% driven by low-ticket, high-frequency baskets surfaced by AI-powered recommendation loops. In this context, AI is a demand creation engine.

However, this same mechanism creates pressure. If AI raises the conversion efficiency of e-commerce platforms, advertisers and merchants shift budgets heavily toward the ecosystems that deliver the highest return on ad spend (ROAS). This benefits platforms that own the checkout, but it marginalises companies dependent on top-of-funnel traffic.

AI therefore strengthens retail media inside Shopee and Lazada, and weakens traditional performance marketing dependence on Google and Meta. In other words, AI amplifies platform economics for those who are already platforms, and threatens the economics of those who sit outside the transaction.

AI is also transforming food delivery through algorithmic personalisation. Advertising revenue in food delivery is growing 60-90% year on year, and this acceleration is only possible because platforms are serving ads and restaurant listings based on context, time of day, demand forecasting and personalised behavioural triggers.

Transport benefits from AI as well, but the benefits come from a different part of the value chain. The report highlights tiered ride products, subscription bundles and in-app ads as the primary revenue drivers, and AI acts as the silent optimisation layer inside pricing, matching and segmentation.

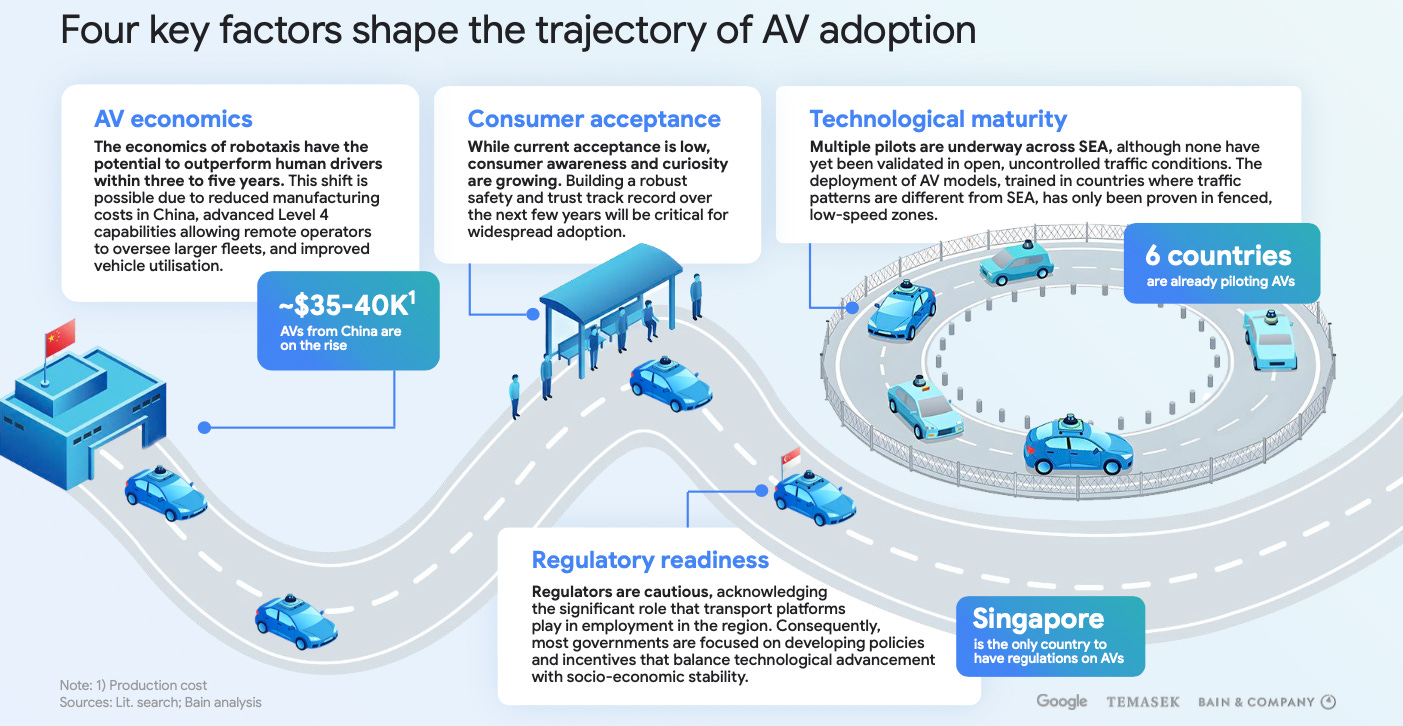

However, transport also illustrates the long-term risk side of AI. Autonomous vehicle unit economics may begin outperforming human-driven models within 3 to 5 years, due largely to China-driven reductions in manufacturing cost to $35-40K per car. If AV platforms scale, the competitive basis in mobility will not be based on driver liquidity. It will be based on capital financing, local operating expertise, safety trust, and regulatory alignment.

Online media demonstrates the volatility of AI more than any other category. Over the past year, there has been a strong acceleration in AI-supported advertising and hyper-localised gaming ecosystems along with a 53% year-on-year rebound in average weekly playtime. While AI grows engagement, it also accelerates competition. Only publishers that execute hyper-local content strategies gain retention advantages.

Short drama is an emerging format and has grown 120% in app downloads and 200% in app active users, a growing sign of short attention span and proving that AI-driven engagement loops reward compressed storytelling and constant novelty.

What AI means for Sea Limited

Shopee is arguably one of the most advantaged AI beneficiaries in Southeast Asia because it controls both sides of the transaction graph. Every buyer action and every seller action feeds into a closed-loop data system that AI can optimise without depending on third-party signals. This gives Shopee a structural edge in personalisation, impulse conversion and frequency uplift.

Video commerce and algorithmic recommendations drive more purchases per user, and they reinforce Shopee’s existing monetisation layers instead of replacing them. AI compounds Shopee’s strengths because Shopee controls the full journey from discovery to checkout.

What AI means for Grab

Grab benefits from AI in its operational intelligence and monetisation stack. AI improves supply matching, pricing, subscription retention and the effectiveness of in-app ads. All of these create higher revenue and better margins without needing more discounts. AI improves the efficiency of mobility and delivery rather than changing the model entirely.

However, there is a long-term uncertainty that does not apply to Shopee. If autonomous vehicles scale widely, supply shifts from labour-driven to capital-driven, and Grab will need to position itself as the demand and routing layer for multiple types of fleets rather than only driver fleets. That said, this is more of a transition risk than a near-term threat.

Lesson #4: Ecosystem lock-in is key

In the first decade of Southeast Asia’s digital economy, platforms competed to be the first app a user downloaded. Today the goal is to be the last app a user deletes. Hence, competitive advantages are determined by who captures the most habit and most spending categories inside a single ecosystem.

This is key particularly in Southeast Asia as switching costs are not driven by storage space or logins, but from loyalty perks, network familiarity, shopping history, embedded payments, saved addresses, personalised incentives, and merchant or restaurant relationships. Once these take hold, users and merchants have strong reasons to stay even when rivals offer discounts. This is very different from the subsidy era when the average user cycled through every platform offering the newest promo code.

I think we can break down the mechanics of lock-in in SEA today to 3 main areas:

Cross-category identity

Embedded financial services

Earn and redeem economics

1. Cross-category identity

The strongest form of retention is when users rely on a platform across multiple consumption functions rather than one. This is why the most successful digital economies globally tend to grow horizontally. In Southeast Asia, cross-category integration has become a defining driver of lock-in.

E-commerce + Logistics (Shopee + SPX Express)

E-commerce/Gaming + Payments (Garena/Shopee + Monee)

Food delivery + Dine-in (GrabFood + Chope)

Mobility + Restaurant discovery (GrabCar + Dine-Out Discovery)

Travel + Payments + Insurance

Online media + creator-driven commerce (TikTok + TikTok Shop)

This is all part of reducing complexity for users, increasing personalisation, accumulating loyalty through rewards in order to attain consumer lock-in. Once users stop thinking of a platform as a single service and start thinking of it as their default way of consuming a category of life, lock-in has already happened.

2. Embedded financial services

Financial services have become the single most powerful driver of platform retention in Southeast Asia. Shopping, mobility and food delivery are high-frequency use cases, but none of them create structural dependence on a single platform. This is why we see every major platform entering the financial services space (Sea and Grab leading the way).

The reason is psychological as much as economic. The user stops comparing platforms as separate apps and starts treating the one they use most as their default financial interface. A user who keeps a balance in ShopeePay or GrabPay is more likely to transact again simply to utilise stored value. But unlike subsidies, stored value does not condition users to chase deals on other platforms. It conditions them to remain within the platform because switching means abandoning money.

3. Earn and redeem economics

This is in my opinion, the strongest lock-in mechanic. Platforms are changing the way they approach rewards. Instead of being a simple: “earn rides, redeem rides” or “earn orders, redeem orders” strategy, platforms are now cross-pushing rewards. For example, Grab would reward a user for taking a ride by offering rewards/discounts on food delivery.

This creates circular consumption where users choose a platform for rides because it gives better value for food, or shop online because it gives better value for mobility. Not every category has to be the most profitable or give the best deals at each time, but simply reinforcing each other creates a strong ecosystem lock-in.

What this means for Sea Limited

Shopee’s strongest moat today is not just delivery speed or low prices but an ecosystem of benefits and behavioural changes. A buyer who has accumulated vouchers, watched creators they trust, used Shopee Pay, and stored return history will not casually migrate elsewhere. Shopee is no longer only a transaction marketplace.

It is the default consumption identity for many Southeast Asian households. When users think of shopping online, they do not weigh three or four platforms. They simply open Shopee, because the trust has already been built over a decade.

What this means for Grab

Grab’s lock-in advantage comes from routine behaviour rather than discretionary behaviour. Users ride to work, commute to dinner, order meals during the week and use mobility while travelling. These actions repeat multiple times per week. This frequency gives Grab a built-in distribution channel for subscriptions, dining perks, cash-back, payments, merchant discovery.

By earning rewards on rides and redeeming them on food, or vice versa, users become locked into the ecosystem even if a rival offers occasional discounts. The more categories a user touches inside Grab, the more the switching cost grows.

The best part is that Grab earns from both the demand and supply end (consumers pay for services, suppliers pay to offer services). Grab as the middle-man platform benefits from being the best aggregator.

Lesson #5: Digital financial services are becoming the core monetisation engine

If the first decade of Southeast Asia’s platform economy was defined by e-commerce, mobility and delivery, the next decade will be defined by digital financial services (DFS). DFS is no longer a side product layered onto shopping or transport. It is becoming the main driver of incremental revenue and incremental margin across the entire ecosystem.

It is therefore no surprise to see major platform players making a concerted effort to grow their DFS segments. (GrabPay, ShopeePay/Monee, GoPay etc)

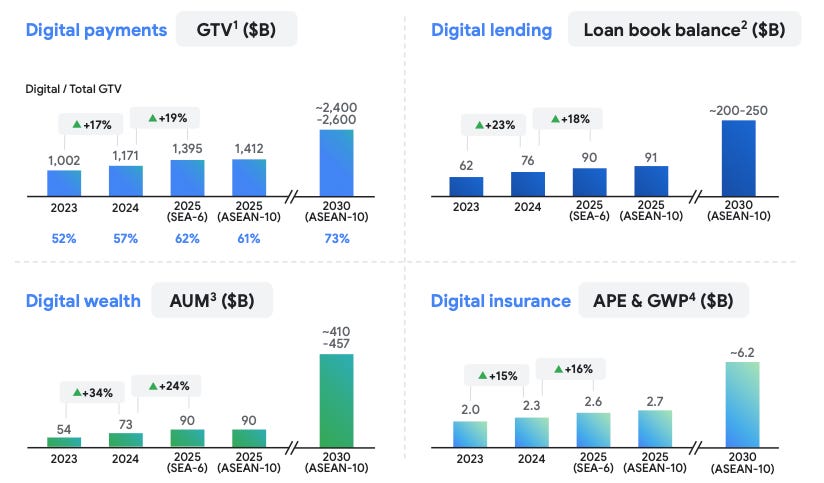

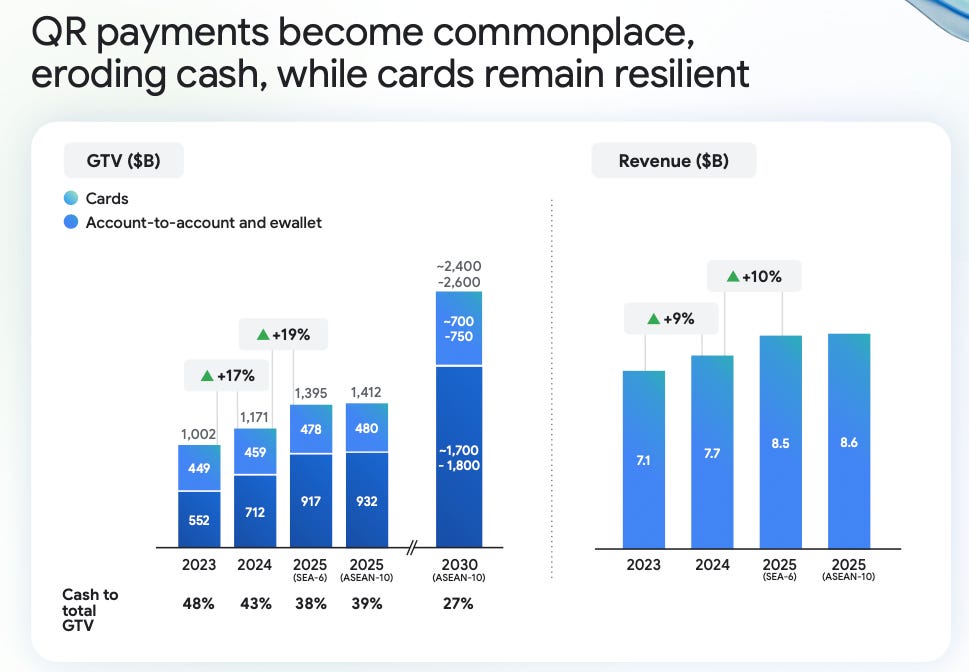

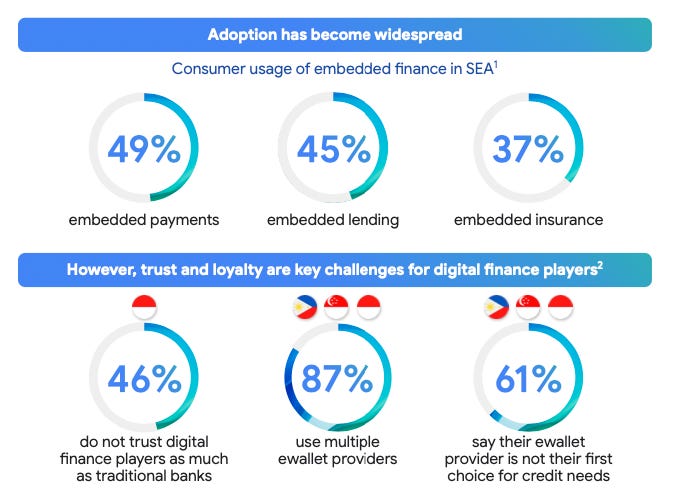

Digital payments account for 62% of total gross transaction value today, a 10pp increase from just 2 years ago. By 2030, it is expected to reach 73% of GTV. Digital lending, wealth and insurance are all growing very strongly and expected to continue a similar growth rate into 2030. Importantly, digital wealth and insurance are increasingly distributed through consumer platforms rather than traditional financial players.

Specifically, DFS matters for three structural reasons:

DFS has the highest incremental margin in the platform stack

E-commerce, mobility and food delivery are generally low-margin businesses that require enormous scale to achieve profitability. Payments, credit, wealth and insurance monetise demand without requiring fleets, logistics infrastructure or physical fulfilment. Each incremental dollar of DFS scales at far higher margin than commerce GMV or transport GMV.

Rides, orders or parcel deliveries have variable cost while payments, loans or insurance policies scale in a different manner. As DFS increases its share of total revenue, platform economics begin to structurally improve.

DFS monetises behaviour that is already happening

Unlike video commerce or dine-in, DFS does not need to change what the user is already doing. It simply monetises the existing economic activity more deeply. Users don’t need to shop, ride or order more. Instead, platforms simply have to enable and incentivise users to pay through the platform instead of externally.

DFS increase retention and reduces CAC at the same time

Once a user stores money, uses platform-issued credit cards or other financial services, the likelihood of churn drastically reduces. These same mechanics simultaneously reduce cost to reacquire users because stored value and repayment schedules act as built-in reactivation triggers.

Why DFS matters more than ever today

Digital financial services are scaling in Southeast Asia today not because platforms suddenly decided to prioritise them, but because the ecosystem has finally reached the maturity required for DFS to work at scale.

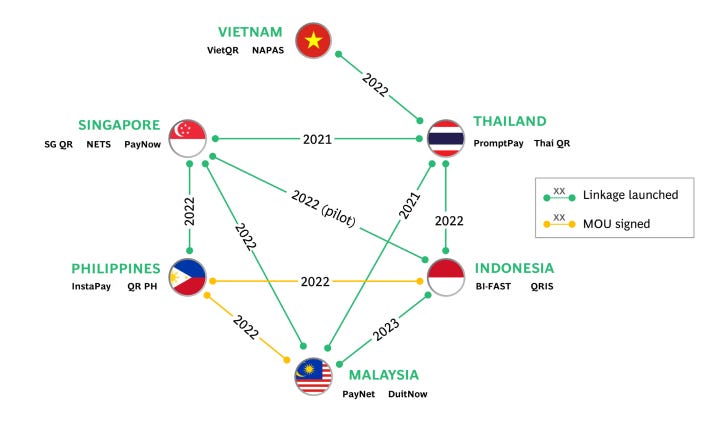

DFS has been present in many platforms’ services for many years, but extra effort and resources have been placed in recent years to accelerate this. The first unlock was payments interoperability. Unified national QR systems and regional cross-border rails removed the fragmentation that once made digital payments inconvenient or unreliable.

The second unlock was consumer trust (although the report does state that trust hasn’t been fully earned yet). Platforms spent a decade proving reliability in logistics, deliveries, mobility and customer support. Only after they became trusted for goods and rides did users feel comfortable storing money, linking cards and accepting credit inside those same platforms.

Lastly, data. Credit cannot scale without the ability to assess risk accurately, and risk cannot be assessed without behavioural and transactional data. After years of high-frequency e-commerce browsing, mobility trips and food orders, platforms now possess the depth of user data required to underwrite loans responsibly and profitably. This is the data advantage that platforms like Sea and Grab possess that I have been harping on for years. Finally, they are beginning to capitalise on that advantage.

For years, the building blocks for DFS were incomplete. Payments lacked reach, platforms lacked trust, and credit models lacked data. Today all three conditions have converged. That is why DFS adoption is accelerating now, and why it will define the next phase of platform monetisation in Southeast Asia.

Lesson #6: Cost discipline is structural, not temporary

For most of 2015-2021, platforms in Southeast Asia behaved as if profitability was optional and continually burned cash in an effort to snatch market share. This was largely fuelled by the ZIRP era where cheap capital flooded the markets in search of ideas.

The inflationary environment globally, brought about by supply-chain disruptions, led to a reset in multiples, particularly in risk assets. Sea and Grab stock fell 80-90% over the ensuing year, which led to tightening of capital, promotional burn becoming intolerable and cash flow discipline becoming a core requirement.

Platforms in SEA have gotten lean. Not just by cutting cost, but by changing the entire design of their economic engines so that growth doesn’t require cost to rise in parallel. Platforms have shifted from paying users to adopt services, to building entire ecosystems that retain users and monetise them. This has been enabled mainly by subscriptions, DFS, cash-back loops and retail media reinforcement.

What this means for Sea Limited

Sea went through the hardest version of this transition. From 2020 to 2022, Shopee relied heavily on promotional subsidies to accelerate adoption and defend market share. It worked well, with them gaining enormous market share, but also led to billions in losses that were funded solely by Garena, its gaming unit.

Since 2023, Shopee has shifted from growth at any cost to stabilised growth, with more focus on monetisation. From the infamous one-ply toilet papers in offices, to shutting its e-commerce operations in Europe and most LatAm nations, Sea aggressively rationalised its cost base.

Today, Sea is an incredibly mean machine where incremental revenue does not require incremental incentive spend. Shopee is now scaling without the burn profile that defined its early years.

What this means for Grab

Grab’s path to profitability used to be controlled by two variables: delivery cost and driver incentives. In other words, its financial outcome was dictated by competition. Management recognised that this left too much of the business’s fate in the hands of rivals, so they shifted the strategy toward scaling high-margin revenue streams (ads, subscription, DFS) to drive monetisation without moderating behavioural volatility on the platform.

Tiered mobility allows Grab to capture willingness to pay at the top end without losing price-sensitive users at the bottom. This means the company can grow revenue even with moderate GMV growth because the cost base no longer expands linearly with volume.

This is why Grab’s margin recovery is much less fragile today than it was pre-2022. Even if competitive intensity rises, the model no longer relies on heavy subsidies to retain users, making profitability structurally more defensible.

Lesson #7: Platforms are becoming more important than Meta and Google in SEA

For over a decade now, Meta and Google have been the centre of the digital advertising universe. Meta boasts nearly 4B active users, while Google dominates search. These platforms controlled purchase intent because consumers searched on Google and browsed on Facebook or Instagram before making a purchase somewhere else.

However, something interesting has happened in this region. Platforms where transactions happen are now gaining more influence over advertising than the platforms where discovery happens. The reason is pretty intuitive when we think about it…

The most valuable signal in consumer behaviour is not awareness or interest but rather intent at the moment of purchase. Whoever controls that, controls the most valuable ad inventory.

I think there are 3 structural changes that have created this shift:

SEA skipped desktop and went straight to mobile-app ecosystems

In the West, e-commerce largely grew through Google → websites → checkout. In SEA, consumers didn’t have the opportunity to build that habit. Instead, they simply open the app → browse → purchase.

SEA platforms integrated payments earlier and more deeply

SEA moved faster on QR interoperability, digital wallets, and BNPL at checkout precisely because they picked up best practices from the West. In the West, cards, PayPal and Apple Pay keep payments external from e-commerce platforms, so the final step happens outside the platform rather than inside it.

Super-app behaviour is normal in SEA

The region had very low digital infrastructure when smartphones arrived. When e-commerce started in the US, people already had laptops, credit cards, desktop websites. When e-commerce started in SEA, none of that was widely adopted. Most users skipped straight to cheap Android smartphones and apps as the primary internet interface.

In SEA, consumers have historically faced traffic/weather unpredictability, long delivery times, fragmented payment options. A single platform to aggregate everything was simply more reliable than juggling disconnected apps. Essentially, consumers rewarded convenience and trust.

Concluding Thoughts

Over the past decade, Southeast Asia’s digital economy has transformed from an insane land grab into a more stable environment focused on profits. The model that used to work of acquiring users at any cost and focusing on monetisation later no longer works.

This report and the data behind it suggests that the next decade is likely to be defined by platforms that can monetise behaviour. GMV will continue to be important, but there are other metrics to focus on such as margins, the depth of the financial stack layered on top of the core service, and revenue mix.

In my mind, there are 3 clear winners in Southeast Asia. Sea Limited, Grab and TikTok. Unfortunately, I am only invested in the first 2 as TikTok remains private.

Sea Limited is perhaps the clearest beneficiary of the region’s structural shifts. Shopee is positioned to be the most advantaged AI and retail media platform in Southeast Asia because it owns the entire transaction loop. The key competition comes from TikTok, with its superior video commerce capabilities. That said, Shopee has partnered with YouTube to counter that, and it appears to be working very well.

Grab is positioned to be the most advantaged mobility and food DFS distributor because it sits on top of weekly spending behaviour. It now has to monetise well in its core segments and spur growth in its adjacent business lines that could one day be the main profit drivers.

For all the reasons above, I remain extremely excited about the opportunity in Southeast Asian markets, particularly the digital economy.

Thanks for reading!

Part 2 will likely be out in the next week.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational and educational purposes only and does not constitute investment, financial, legal, or tax advice. The views expressed are my own and should not be relied upon as a recommendation to buy or sell any securities or financial instruments. Investing in emerging markets involves risks, including but not limited to currency fluctuations, political and regulatory instability, and market volatility. Past performance is not indicative of future results. Please do your own research and consult with a licensed financial advisor before making any investment decisions.

Thank you for sharing it for free!

Great article. What are your thoughts for SEA in Brazil vs Meli? Enough room for both to grow?